The biggest investment we can make to enhance our teaching is to understand the learning process and subsequently tailor our efforts to produce maximal learning (DiPetra, 2021).

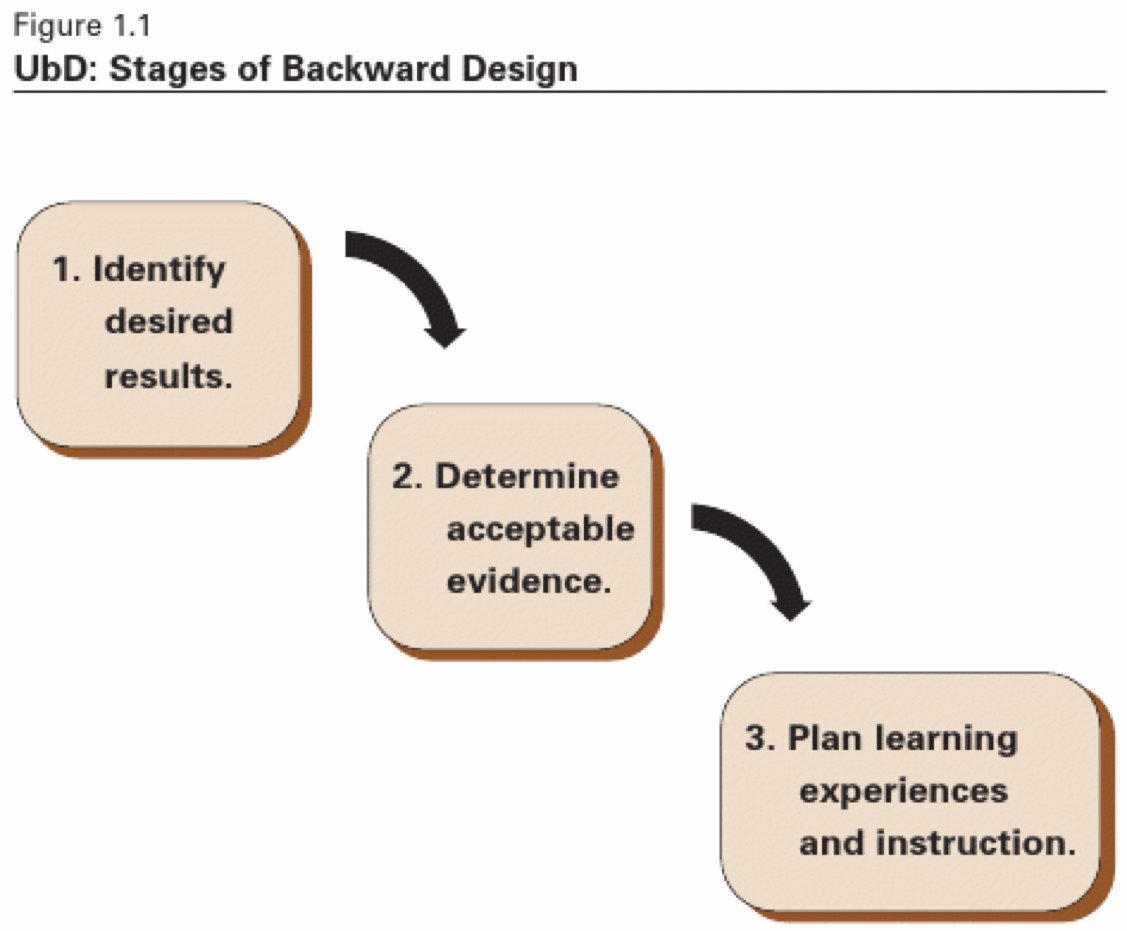

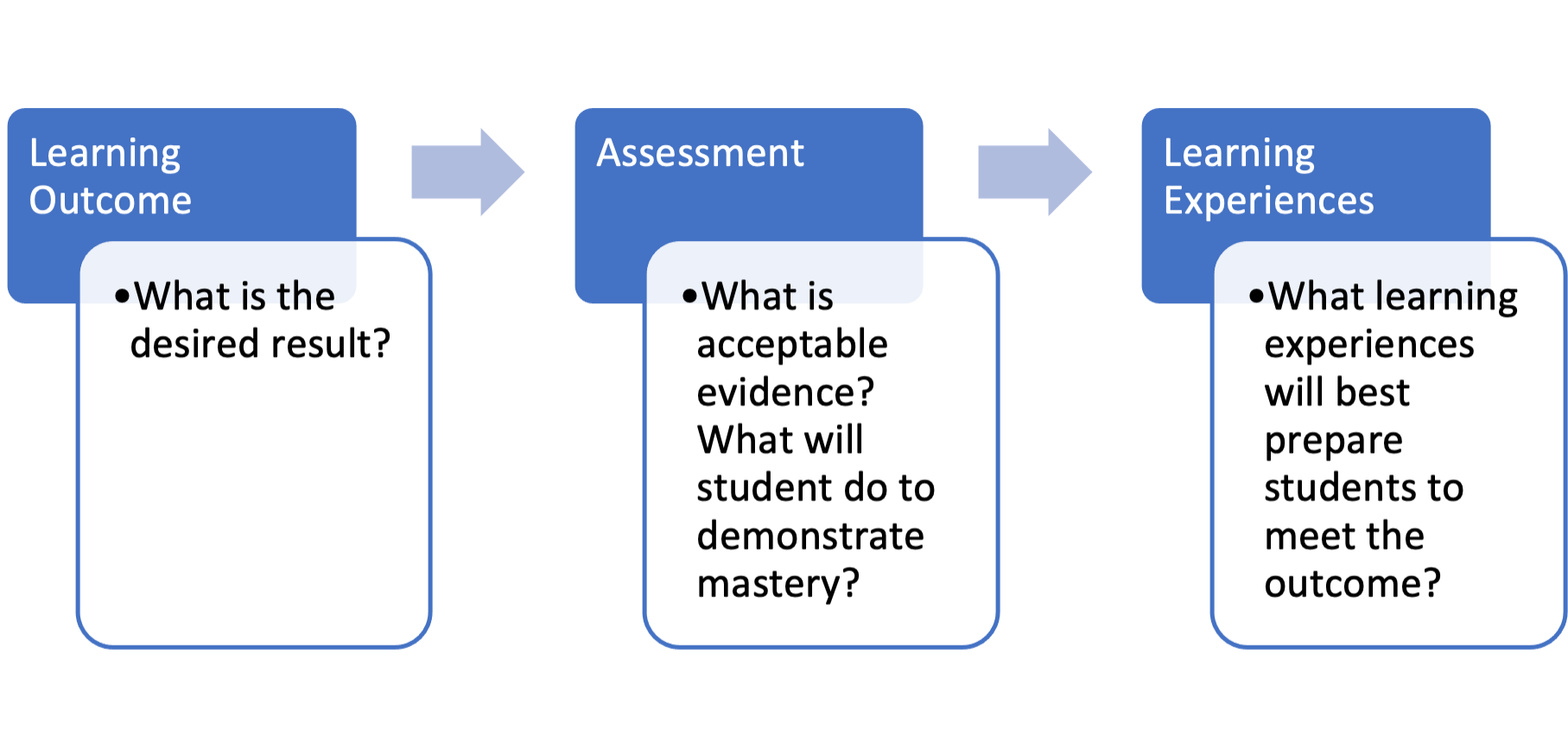

What is Backward's Design (Wiggins & McTighe 1998; Bowen 2017)? Rather than focusing on "how" to teach content, instructors should spend time identifying desired results of student learning and develop assessments to meet these goals. What do you want students to take away from the course? What skills should they develop? These are core concepts and competencies.

What is Backward's Design (Wiggins & McTighe 1998; Bowen 2017)? Rather than focusing on "how" to teach content, instructors should spend time identifying desired results of student learning and develop assessments to meet these goals. What do you want students to take away from the course? What skills should they develop? These are core concepts and competencies.

Examples of core concepts and competencies (adapted from informED):

How will students be able to know they have succeeded in learning the core concepts and competencies? How will you, as the instructor, know they have met the goal? Consider various forms of both formative and summative assessment (see more in the assessment tab below).

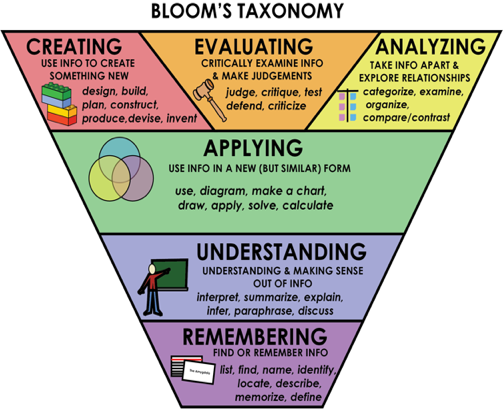

Practice this process using this template. In this template, think of goals as the course learning outcomes (CLOs), the essential understandings as the core concepts and competencies, and performance tasks as the learning objective.

Consider the content. Do students need to know this to succeed in obtaining the core concepts and competencies? By creating a curated framework, instructors can teach students how to learn in the discipline rather than focusing on content coverage (Peterson et al. 2020).

Petersen, Christina I., et al. "The tyranny of content:“content coverage” as a barrier to evidence-based teaching approaches and ways to overcome it." CBE—Life Sciences Education 19.2 (2020): ar17. https://www.lifescied.org/doi/10.1187/cbe.19-04-0079

Wiggins, Grant, and McTighe, Jay. (1998). Backward Design. In Understanding by Design (pp. 13-34). ASCD.

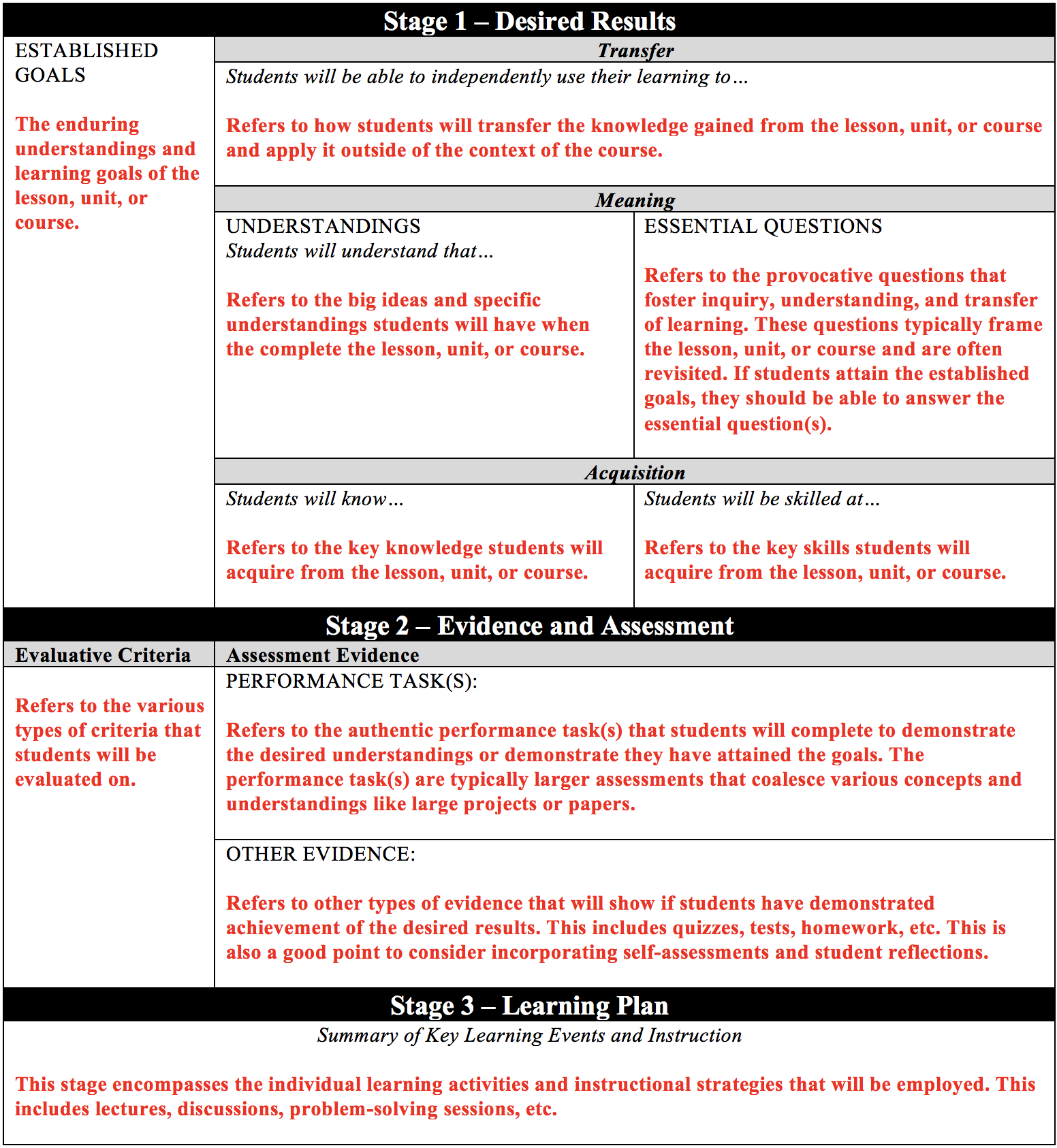

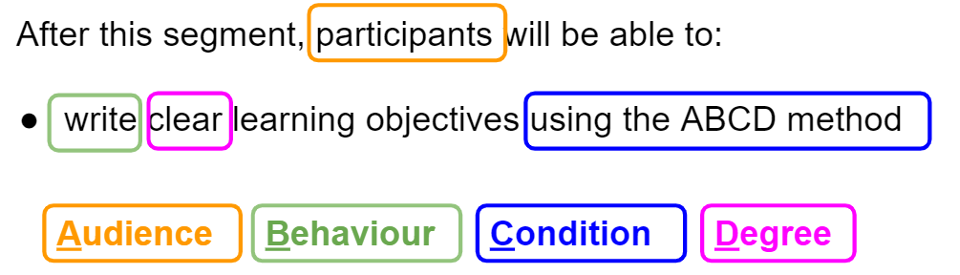

In 1956, Benjamin Bloom with collaborators Max Englehart, Edward Furst, Walter Hill, and David Krathwohl published a framework for categorizing educational goals: Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Familiarly known as Bloom’s Taxonomy, this framework has been applied by generations of K-12 teachers and college instructors in their teaching. A well-written learning outcome will help you determine appropriate assessment tasks and plan appropriate and targeted learning experiences.

In 1956, Benjamin Bloom with collaborators Max Englehart, Edward Furst, Walter Hill, and David Krathwohl published a framework for categorizing educational goals: Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Familiarly known as Bloom’s Taxonomy, this framework has been applied by generations of K-12 teachers and college instructors in their teaching. A well-written learning outcome will help you determine appropriate assessment tasks and plan appropriate and targeted learning experiences.

Course learning outcomes are similar to core concepts and competencies. They describe an overarching purpose of the course and the intended results the students should obtain through the learning experiences. They reflect what the students will say, hear, or do as a result of the learning experiences. They are broad, measurable, student-centered, and explicitly describes what the learner should be able to demonstrate to achieve the desired results. At UC Merced, each course has designated Course Learning Outcomes (CLOs). CLOs are often developed when the course is created and are approved through the Academic Senate. You can find approved CLOs for your course using Curriculog.

Course learning outcomes are similar to core concepts and competencies. They describe an overarching purpose of the course and the intended results the students should obtain through the learning experiences. They reflect what the students will say, hear, or do as a result of the learning experiences. They are broad, measurable, student-centered, and explicitly describes what the learner should be able to demonstrate to achieve the desired results. At UC Merced, each course has designated Course Learning Outcomes (CLOs). CLOs are often developed when the course is created and are approved through the Academic Senate. You can find approved CLOs for your course using Curriculog.We have known for some time that high levels of stress and anxiety can wreak havoc on our overall health.

In cognitive psychology, cognitive load refers to the amount of resources in working memory that are being used by students for processing and encoding new information. We understand that some level of difficulty and challenge is beneficial during the learning process, but when cognitive load is too high, frustrations rise, comprehension suffers, and some students give up completely. Reducing excessive and/or extraneous cognitive load is completely in the hands of the instructor. In 2017, Malamed, an e-learning coach, argues, “by reducing the extra mental effort required to learn new information, we can assure greater learner success” (Malamed, 2017, Par. 3). While we have little control over the demands placed on our students outside of the educational environment, we can take steps to reduce the extraneous load placed on students during the learning process.

Lukasik, K. M., Waris, O., Soveri, A., Lehtonen, M., & Laine, M. (2019). The relationship of anxiety and stress with working memory performance in a large non-depressed sample. Frontiers in Psychology, 10:4. Doi 10:3389/fpsyg.2019.00004.

Malamed, C. (2017). Six strategies you may not be using to reduce cognitive load. The eLearning Coach (www.theelearningcoach.com).

Moran, T. P. (2016). Anxiety and working memory capacity: a meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 142, 831-864. Doi 10.1037/bul0000051.

Plass, J. L., Moreno, R., & Brünken, R. (2010). Cognitive Load Theory. New York, New York: Cambridge Press.

Land Acknowledgement (from OEDI)

Land Acknowledgement (from OEDI)A Land Acknowledgement is a formal statement that recognizes the unique and enduring relationship that exists between Indigenous Peoples and their traditional territories.

To recognize the land is an expression of gratitude and appreciation to those whose territory you reside on and a way of honoring the Indigenous people who have been living and working on the land from time immemorial. It is important to understand the long-standing history that has brought you to reside on the land, and to seek to understand your place within that history. Land acknowledgments do not exist in a past tense, or historical context: colonialism is a current ongoing process, and we need to build our mindfulness of our present participation. It is also worth noting that acknowledging the land is Indigenous protocol.

Statement for the first day of class:

“We pause to acknowledge all local indigenous peoples, including the Yokuts and Miwuk, who inhabited this land. We embrace their continued connection to this region and thank them for allowing us to live, work, learn, and collaborate on their traditional homeland. Let us now take a moment of silence to pay respect to their elders and to all Yokuts and Miwuk people, past and present.”

It starts with the syllabus, followed by the course learning outcomes

It starts with the syllabus, followed by the course learning outcomesNeed some inspiration to get started? Read Professor Chanelle Wilson's process of revising and decolonizing their syllabus.

Are our curriculum and syllabus language welcoming diversity of thought and validating multiple perspectives or is it by nature exclusionary? We serve a diverse group of students and future scholars. In these times of social and political unrest, it behooves us to examine our curriculum (i.e., What is common knowledge in the discipline and why is it common while other knowledge is less so or even denied?), as well as the language used in our syllabi. This is the work necessary to begin the process of decolonizing our curriculum.

Reconstruct your syllabus with these ideas in mind

Introduce who you are and your background. It matters that students see you for you.

Create community norms with your students and include language that addresses intolerance of microaggressions and racists remarks, actions, and behaviors.

Build flexibility into your communication methods, assessment, and grading. Allow room for mistakes and growth.

Make materials, examples, and assignments inclusive to race, socio-economic standing, gender, sexuality, disability, immigration status, English language learner, and first-generation students.

Offer positive affirmations and supportive language throughout your Canvas and communications with students (asset vs. deficit thinking).

Include information about affordable housing, psychological services, food security, academic support, etc.

" Decolonizing involves identifying colonial systems, structures and relationships, and working to challenge those systems. It is not 'integration' or simply the token inclusion of the intellectual achievements of non-white cultures. Rather, it involves a paradigm shift from a culture of exclusion and denial to the making of space for other political philosophies and knowledge systems. It's a culture shift to think more widely about why common knowledge is what it is, and in so doing adjusting cultural perceptions and power relations in real and significant ways" (Keele Decolonizing the Curriculum Network, 2020).

Validation

Engagement

Ahadi, H. S., Guerrero, L. S. (2020) "Decolonizing Your Syllabus, an Anti-Racist Guide for Your College" Academic Senate for California Community Colleges. URL

Rendon, L. (1994) “Validating Culturally Diverse Students: Toward a New Model of Learning and Student Development.” Innovative Higher Education 19.1: 33-51.

Strayhorn, T. (2018) College Students’ Sense of Belonging: A Key to Educational Success for All Students. ISBN 9781138238558

Instructors and students alike are often surprised when the results of a mid-term or final examination expose knowledge gaps, misconceptions, and/or students' inability to accurately apply newly acquired information in novel situations. But according to research, this is very common in classrooms today (Ambrose, et al., 2010). Our assessment procedures often reveal where there is a lack of coherence or misalignment among course design components (Saroyan & Amundsen, 2004). To adequately prepare students for successful learning and performance on our assessments, we must understand the:

This guide is designed to help you think more intentionally about the use of assessment in your courses.

References:

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: the classification of educational goals; Handbook I: Cognitive domain. In M. D. Engelhart, E. J. Furst, W. H. Hill, & D. R. Krathwohl (Eds.), Taxonomy of educational objectives: the classification of educational goals; Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay.

Saroyan & Amundsen, (2004). Rethinking teaching in higher education: From a course design workshop to a faculty development framework. Sterling, VA: Stylus Pub.

Type of Knowledge |

Description |

Examples |

Declarative orcontent knowledge |

knowing what; facts and other information that can be declared |

1. Identifying the structure and function of an animal cell. 2. Describing the difference between an artery and a vein. 3. Identifying the strengths and challenges of general research design methods (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, or mixed). 4. Knowing a variety of statistical analyses. |

Procedural or process knowledge |

knowing how; being able to work through a process or procedure

|

1. Using different types of microscopes to study cells/stains. 2. Designing a qualitative research study. 3. Performing a mathematical formula or algorithm. |

Conditional knowledge |

knowing when and why; recognizing the conditions under which declarative or procedural knowledge is to be used. |

1. Selecting the correct statistical analysis to analyze a data set based on the research question and other factors. 2. Developing new policies and/or practices to keep students and staff safe during the pandemic. |

Consider the different types of knowledge presented in your course content and materials. Do your planned learning activities/exercises facilitate the development of each type of knowledge? Most importantly, have you created learning experiences for students that will help them develop conditional knowledge?

References:

Anderson, L.W. & Krathwohl, D.R. (Eds.), et al. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objective. In P. W. Airasian, K. A. Cruikshank, R. E. Mayer, P. R. Pintrich, J. Raths, & M. C. Wittrock (Eds.), A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: the classification of educational goals; Handbook I: Cognitive domain. In M. D. Engelhart, E. J. Furst, W. H. Hill, & D. R. Krathwohl (Eds.), Taxonomy of educational objectives: the classification of educational goals; Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay.

Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L., & Cocking, R.R. (2000 Eds.). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1st edition.

The purpose of assessment is to diagnose, monitor, and direct student learning, make informed decisions about your curriculum and instructional methods, and ultimately evaluate students. As you begin to think more about the importance of assessment in evaluating the effectiveness of your teaching and assessing student learning, ask yourself:

How can I best monitor student progress toward the course learning outcomes or lesson objectives?

What is the most effective and authentic (i.e., close to real-world applications) way to evaluate student mastery of these CLOs?

What do the student assessment results tell me about my curriculum and instructional choices (i.e., Are these effective? Do I need to augment materials or activities? etc.)?

Let's look at two types of assessment: Formative and Summative (Scriven, 1981).

|

Type of Assessment |

Purpose or Use of Data is to: |

Best Serves |

|

|

Formative |

"FOR" Learning

|

To diagnose needs or monitor student progress and inform upcoming instructional planning/decisions. |

Instructor |

|

"AS" Learning

|

To enhance student development as self-directed learners, focus learners, and help students identify effective study strategies. |

Students |

|

|

Summative |

"OF" Learning

|

To evaluate/judge a) student performance on CLOs and/or lesson objectives, and b) the effectiveness of instructional materials and activities. |

Instructor |

If our goal is to improve student performance and persistence, then we must employ frequent and diverse forms of formative, low-stakes (or no-stakes) assessments and use the results to inform future lessons. These results should also inform students about their progress and perhaps illuminate where they might need to focus their attention and study. Some possible strategies are:

Application-oriented in-class learning activities/exercises (e.g., labs, creating concept maps; solving problems)

Brief reflections (e.g., minute papers, exit tickets, entrance tickets)

Weekly quizzes as low stakes, checks for understanding among students. These could be a mixture of lower-level terminology items and higher-level analysis, synthesis, and/or application questions.

Non-graded quizzes; iclicker questions; polling; minute papers; reflective entrance or exit tickets; lab reports; weekly exercises/homework, etc. to help students monitor their own progress.

Open book/Open notes exams (or even collaboratively with a peer).

Multiple choice and/or short answer exam questions that ask them to synthesize information.

Authentic tasks, case studies, completed individually or in small groups.

Require students to extrapolate from data and apply it to a situation they have not yet encountered in the class.

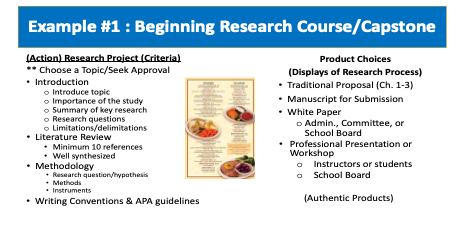

Grading student performance in relation to the course learning outcomes is an important part of the instructor's job. In addition to the variety of formative assessments along one's journey toward mastery of core concepts and competencies, you will want to employ some more evaluative assessments to judge mastery of the CLOs. These summative assessments can be as diverse as the ways in which students learn. For example:

Traditional mid-term and final exams

Papers, essays, poster sessions

Special performances

Podcasts or video demonstrations

Open-ended, complex, and authentic projects or design challenges

The purpose of assessment shifts from the assessment “of” student learning (i.e., for the purpose of grading, reporting, and evaluating) to the assessment “for” and "as" student learning (i.e., to make decisions that improve student learning and development).

Instructors utilize ongoing, informal formative assessment techniques that commonly (but not always) have nothing to do with grading (Saroyan & Amundsen, 2004). These techniques include written reflections (e.g., the clearest and muddiest point, exit ticket, iClicker or polling questions), discussions, non-verbal behavior (e.g., deer-in-the-eyes), conversations before or after class, journals, practice performances, and class participation. Again, most often these are no- or -low-stakes assessments.

Rather than use frequent assessments as accountability measures to ensure students are reading and showing up to class (i.e., reward/punishment), instructors design a variety of assessment activities that

Instructors are concerned with developing self-directed, autonomous learners. Giving students choice has been shown to increase student motivation, performance, and autonomy (Ambrose, et al., 2010; Evans & Boucher, 2015).

Who said everyone needs to write a final paper? Why not let students have a say in how they demonstrate their learning? If the assignment expectations and grading criteria are clearly communicated to students (see rubric information below), there is no need to force everyone into the same type of performance. This does not imply that you won't ever require the same assignment of all students; rather, that you will think about when different performances or products can demonstrate the same expectations.

Review the type(s) of assessment (formative and/or summative) currently being used in your course. Are you currently providing students with multiple, no- or low-stakes opportunities to assess their own progress and adjust their efforts? Are students being asked to apply new information and skills in ways that are authentic to the discipline? In what ways might you do a better job of assessing the different types of knowledge?

References:

Evans, M., & Broucher, A. (2015). Optimizing the power of choice: Supporting student autonomy to foster motivation and engagement in learning. Mind, Brain, and Education, Vol 9 (2), 87-91. DOI: 10.1111/mbe.12073

Saroyan & Amundsen, (2004). Rethinking teaching in higher education: From a course design workshop to a faculty development framework. Sterling, VA: Stylus Pub.

Scriven, M. (1081) Evaluation thesaurus (3rd ed.). Inverness, CA: Routledge.

From the student's perspective, what we assess signals what we think is important and what we want students to learn; it defines the actual curriculum. For example,

if our course assessment plan consists primarily of multiple-choice tests requiring recall of information, this tells students to focus on learning specific information (i.e., shallow learning). If our assessment plan requires students to work through cases in which they propose not only solutions but also their rationales, this sends a message that deep learning (i.e., critical thinking) is important (Saroyan & Amundsen, 2004, 97).

How students perform on an exam or final performance is as much a reflection of what they were asked to do during the learning process as it is about the design of the assessment itself. For example, students often take notes during a live or recorded lecture, complete recall-oriented assignments and/or performances, participate in discussions, and complete multiple-choice quizzes or iClicker questions to master the learning outcome and prepare for the upcoming exam. But unless these multiple-choice items assess conceptual understandings or require the application of new information, student learning will be shallow and focus on memorization for recognition purposes (Ambrose, et al., 2010; Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000). Too often, the type of questions posed to students on quizzes, polling exercises, or practice assignments does not prepare students for exam questions that require them to solve authentic, real-world problems, evaluate policies, or produce creative works.

For any type of classroom assessment measure to be valid, it must measure learning that is stated in the course learning outcomes (CLOs). And from a design perspective, learning outcomes and assessments drive the selection of planned learning experiences, including content delivery, practice assignments, quizzes, discussions, etc. (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005).

When a course is designed coherently, the planned learning experiences "provide students with sufficient practice and feedback to enable them to accomplish the desired learning and be prepared for evaluation activities" (Saroyan & Amundsen, 2004, 98).

Take an honest look at course alignment. Ask yourself the following:

Are the CLOS clear, observable, and measurable statements of expected knowledge, skills, and dispositions?

Do CLOs reflect core concepts and competencies for the level of this course (i.e., intro., lower or upper-division, graduate-level)?

Do you have a variety of formal and informal assessments, with more frequent formative assessments to monitor and direct student learning?

Taken together, are the assessments a solid reflection of the CLOs/expectations for students?

Do the planned learning experiences (LEs) for your course (i.e., content delivery, practice exercises, discussions, group work, assignments, etc.) adequately prepare students for the type of summative assessment utilized in each unit of study.

Do your assessments target lower- or higher-order thinking skills?

Are there ways you can improve the alignment of the LEs and assessments?

References:

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L., & Cocking, R.R. (2000 Eds.). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1st edition.

Saroyan & Amundsen, (2004). Rethinking teaching in higher education: From a course design workshop to a faculty development framework. Sterling, VA: Stylus Pub.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd Ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Have you ever heard any of the following from your students?

Why did you give me this grade?

You didn't even lecture about that topic!

You never told us that we would be graded on spelling or grammar!

How were we to know you wanted X?

Susie and I studied together, yet you gave her an A and I got a C. Why?

For most faculty, grading (sometimes referred to as marking) is one of the most undesirable aspects of the job. To promote student growth and development, grading requires providing students with frequent and instructive feedback, both of which can be time-consuming and present other challenges. According to Saroyan & Amundsen (2004), most instructors are concerned with how to

manage assessment and grading in large classes

grade group work and class participation

increase reliability among multiple graders (TAs)

increase objectivity when marking

handle grading disputes (95).

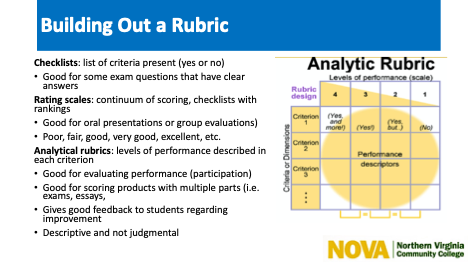

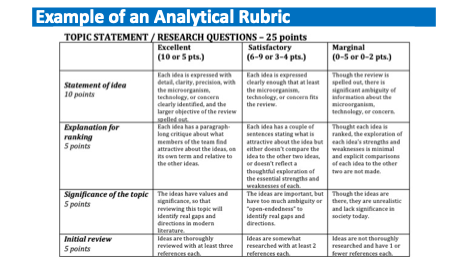

While these are all important issues related to grading, we want to focus your attention on one specific grading technique - the development and use of rubrics, which have the potential to mitigate many of the concerns noted above. Additionally, grading rubrics can be used to assess a range of activities in any subject area.

Reflect on the following questions and resources:

What is a grading rubric?

A rubric is an explicit set of criteria used for assessing a particular type of work or performance, and it provides more details than a single grade or mark. Rubrics, therefore, will help you grade more objectively and efficiently (Stevens & Levi, 2005).

What are the benefits of using a grading rubric?

Rubrics are useful for instructors and students alike:

|

Instructor Benefits Rubrics: |

Student Benefits Rubrics: |

|

help clarify and communicate assessment/performance expectations |

help clarify assessment/performance expectations; clarity on what constitutes different levels of performance (grades). |

|

provide more objective, consistent, and equitable grading of a range of student performances, assignments, and learning activities |

if given to students along with the assessment/assignment, a rubric can show students how to meet expectations, making students more self-directed in their learning |

|

ensure timely and constructive feedback |

provide feedback that is more detailed, instructive, and specific in terms of how to improve one's performance on revised or subsequent work |

|

can reduce grading time |

increases the likelihood that students will include required elements of an assignment |

|

can help to rationalize grades when students ask about your method of assessment (reduce grading disputes) |

help illuminate specific areas where the student may need to exert more effort or improve skills. |

|

provide a vehicle for increasing reliability among multiple graders (especially if you conduct grading calibration exercises). |

|

|

serve as good documentation for accreditation purposes |

|

What are the elements of a rubric?

Most commonly, a grading rubric is designed in a matrix or grid-type structure and includes grading criteria, levels of performance, the range of possible scores, and descriptors that serve as unique assessment tools for a specific assignment/assessment. There are different types of rubrics (e.g., checklists, rating scales, and analytic), each serving a different purpose (see Figure 1). The most common, however, is the analytic rubric (see Figure 2).

Figure 1

Figure 2

The biggest investment we can make to enhance our teaching is to understand the learning process and subsequently tailor our efforts to produce maximal learning (DiPetro, 2021).

Engagement is the necessary first step for learning (Cavanagh, 2019).

Students are unique and require various techniques to get them engaged in class. This requires intention and planning.

References

Cavanagh, S.R. (2019). How to make your teaching more engaging: Advice guide. Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved on Aug 10, 2020, at https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-to-make-your-teaching-more-engaging

DiPetro, M. (2021). How learning works: The Seven Learning Principles. Retrieved on July 16, 2021, at https://cetl.kennesaw.edu/how-learning-works-seven-learning-principles

Trowler (2020) defines student engagement as the investment of time, effort and other relevant resources by both students and their institutions intended to optimize the student experience and enhance the learning outcomes and development of students and the performance, and reputation of the institution (p. 6).

The National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) describes engagement as a multi-dimensional construct influenced by both individual and institutional characteristics (Kuh, 2009). In other words, engagement is a function of both a student's intrinsic desire and the extrinsic opportunities provided by the institution to engage with the course content (Axelson & Flick, 20011; Harper & Quaye, 2009; Trowler, 2010).

Engagement in the classroom falls within three categories: behavioral, cognitive, and affective (Fredericks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004). These three types are distinct yet interrelated.

Behavioral engagement conveys the presence of general "on-task behavior." This entails effort and persistence along with paying attention, asking questions, seeking help that enables one to accomplish the task at hand, and not disrupting instruction. It is the observable act of students being involved in learning.

Cognitive engagement connotes investment aimed at comprehending complex concepts and issues and acquiring difficult skills. It conveys deep (rather than surface-level) processing of information whereby students gain a critical or higher-order understanding of the subject matter and solve challenging problems. Cognitively engaged students often go beyond the requirements because they enjoy being challenged.

Affective/Emotional engagement connotes emotional reactions linked to task investment. The greater the student's interest level, enjoyment, positive attitude, the positive value held, curiosity, and a sense of belonging (and the less the anxiety, sadness, stress, and boredom), the greater the affective engagement. Based on current research and understanding, we don't know how the three types of engagement interact, and we are not certain which antecedents are linked to which types" (Ladd & Dinella, 2009).

*** We also know that our affective/emotional state can impact levels of engagement. Trauma affects students’ executive functioning and self-regulation skills. That means they will have a harder time planning, remembering, and focusing on what they need to learn (Imad, 2020).

References

Axelson, R.D. & Flick, A. (2010) Defining Student Engagement, Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 43:1, 38-43, DOI: 10.1080/00091383.2011.533096

Fredricks, J.A., Blumenfeld, P.C. & Paris, A.H. 2004, "School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence", Review of Educational Research, vol. 74, no. 1, pp. 59-109.

Harper, S.R. & Quaye, S.J. (Eds) (2009). Student Engagement in Higher Education, Routledge, New York & Oxon.

Imad, M. (2020). Leveraging the neuroscience of now. Inside Higher Education, June 3, 2020

Ladd, G.W. & Dinella, L.M. (2009). Continuity and change in early school engagement: predictive of children's achievement trajectories from first to either grade? Journal of Educational Psychology, 101 (1), 190-206. DOI: 10.1037/a0013153

Trowler, V. (2010). Student engagement literature review. The Higher Education Academy, July 2010. Retrieved on August 10, 2020, at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322342119

|

Ideological Perspective |

Educational Ideology in Relation to Teaching |

Role of Students |

Implications for Engagement |

|

Traditionalism |

Teaching is about transmitting information, induction into the discipline. Information transfer/teacher-focused approach. |

Learning through absorbing information provided to them. |

Students need to be interested in the content. Students participate by attending lectures and complying with behavioral norms. |

|

Progressivism |

Teaching is about developing students‟ minds so they can better appreciate the world, about making them autonomous. Conceptual change/student- focused approach. |

Learning through co-construction of knowledge. |

Students need to be engaged in, and with, learning – both in and out of the classroom. |

|

Social Reconstructionism |

Teaching is about empowering students to see the inequities and structured nature of advantages and disadvantages in the world and to change it. |

Students need to be engaged in, and with, learning – both in and out of the classroom. |

Students need to be engaged with the world beyond the classroom, challenging and changing structural inequity. |

|

Enterprise |

Teaching is about giving students the skills to thrive in their careers and to contribute to the economy.

|

Learning through the application of knowledge across disciplinary boundaries to real-life practical problems. |

Students need to be engaged in work-based / vocational learning Students need to be engaged in work-based / vocational learning. |

References

Trowler, V. (2010). Student engagement literature review. The Higher Education Academy, July 2010. Retrieved on August 10, 2020, at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322342119

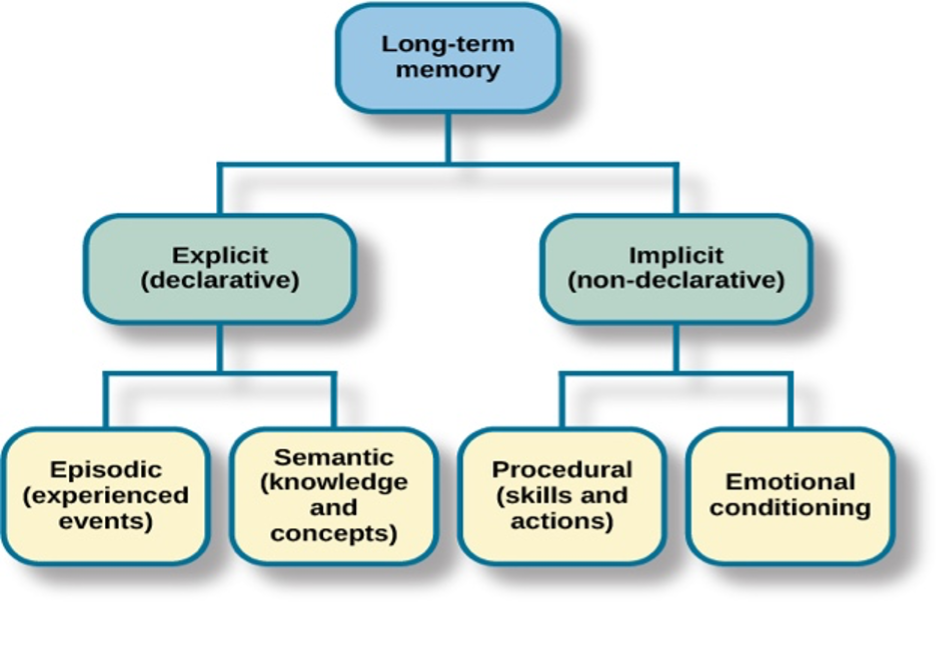

Chunking content into shorter time periods, smaller learning segments, and using emotional hooks to tap into episodic memory will help reduce cognitive load.

Stimulate interest, curiosity, and participation.

Tap into students’ emotions and lived experiences:

Brief lesson teasers

Stories or images

Music/Songs

Provocative questions

Current events/headliners

Demonstrations

Videos

Case studies or simulations

An example might be to present Public Health students with the Flint Water Crisis:

The Flint water crisis is a public health crisis that started in 2014, after the drinking water source for the city of Flint, Michigan was changed. In April 2014, Flint changed its water source from treated Detroit Water and Sewerage Department water to the Flint River.

What questions, issues, or perspectives come to mind as you analyze this situation?

What do you know about the water here in the Central Valley of California? What, if any, challenges exist and why?

Based on what you learned in researching the Flint Water Crisis, what recommendations might you have for Californians?

Whether you like it or not, the reality is your presence makes a difference in student engagement.

Students report choosing their major based on taking introductory courses with, particularly dynamic professors – help your student fall in love with the subject.

Research indicates that the instructor’s enthusiasm is contagious and helps predict variables like student motivation in the course.

Take risks and try new things. Interject current events that make the material more relevant or that add value to the discipline.

Be explicit about the performance expectations and the value of this material.

Build academic supports to help build confidence and expectancy levels.

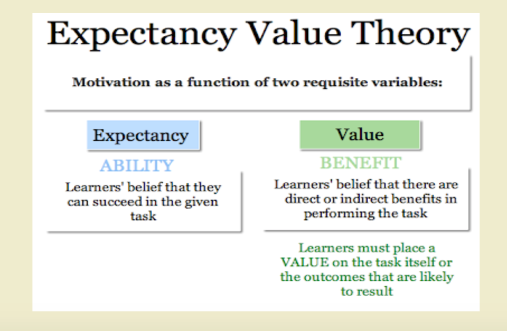

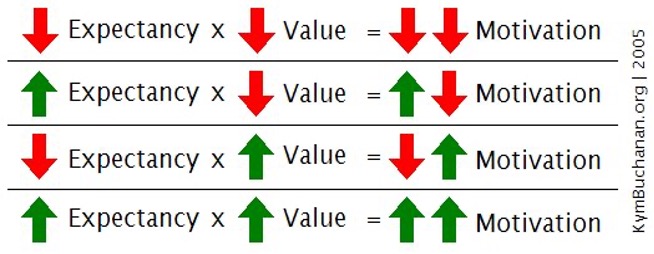

Motivation and/or levels of interaction with the course content is driven by one's expectations to succeed and the value the individual places on the material.

Learning is a social act. Discussions and collaborative work, whether asynchronous or synchronous, help students process, elaborate on, and make connections between and among new information and prior knowledge (Ambrose, et al., 2010).

Learn/use student names

Provide opportunities for everyone to contribute – jigsaw content & assign roles

Work as a class on a shared project; perhaps replace final exam (e.g., create a children’s book on the topic). Utilize the arts and humanities to build interest and variety.

An example asynchronous discussion board for Microbiology might be:

Of all the types of memory, episodic is said to be the most powerful in terms of deep, lasting memory for retrieval purposes. Episodic memory is a type of declarative memory that allows you to consciously recall personal experiences and specific events that happened in the past (Tulving, 2002).

The stories you tell in your classroom can be about your own intellectual path, your research/fieldwork, about people who have lived through different historical eras, about patient case histories. Whatever their type or shape, tell stories.

Your students also have relevant stories to tell – inviting these stories demonstrates to students your interest in them and their potential for contribution to your course and the field (Cavanagh, 2019).

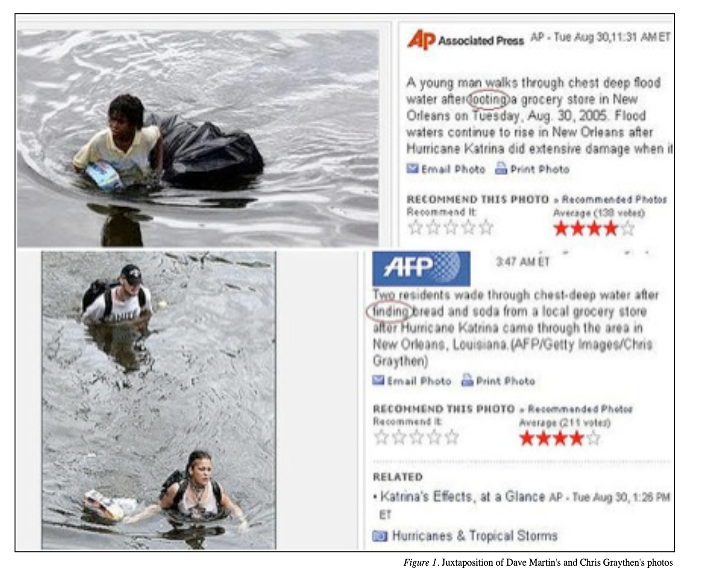

An example of taping into episodic memory is: Lesson: Word Choice Matters!!

In the Aftermath of Katrina (2005), these two photographs appeared on Yahoo News and other Internet news outlets on September 2nd, 2005. Analyze the socio-political impact of journalists choosing the words “looting” over “finding.”

References

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Cavanagh, S.R. (2019). How to make your teaching more engaging: Advice guide. Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved on Aug 10, 2020, at https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-to-make-your-teaching-more-engaging

Tulving, E. (2002). Episodic memory: From mind to brain. Annual Review Psychology, 53:1–25. Retrieved July 16, 2021, at https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.13...

Moore (1989) points out that

"many of our greatest problems of communicating about concepts, and therefore, [educational] practice ... arise from our use of crude hypothetical constructs - terms like... interaction... [because] the same terms are commonly used at both generic and more specific levels" (p. 1). Interaction is one of those terms that need definition. When we think of student engagement, Moore's (1989) distinct types of interaction are very useful: learner-content, learner-learner, and learner-instructor interaction.

Authentic and Meaningful Tasks: real-world, challenging applications/tasks in the discipline. Some examples include case studies, lab experiments, simulations, conducting research, jigsaw activities, presentations/ performances, etc.

Valuable Work: important work that facilitates deep and lasting learning (i.e., processing - encoding - retrieval; reflection and elaboration). Some examples include minute papers, clicker questions/polling or low-stakes quizzes, responding to generative questions or problem-sets true to the discipline, etc.

This second form of interaction, between and among learners, is often a valuable resource for clarifying understandings, correcting misconceptions, and extending learning. Group work also provides an opportunity for students to learn the skills of communication, collaboration, negotiation, and decision- making which are vital to a high-functioning workforce.

Groups: provide clear prompts or tasks and assign roles. Offer opportunities for "think-pair-share and other group activities, assignments, and projects.

The third type of interaction is that between the learners and the content expert (i.e., the instructor). Moore (1089) notes that "the frequency and intensity of the teacher's influence on learners when there is learner-teacher interaction is much greater than when there is only learner -content interaction" (p. 2).

Live interaction: In-person class discussions and office hours; online chats and zoom breakout rooms are effective if teaching online.

Motivate Deeper Thinking: ask specific questions that facilitate processing, elaboration, and application, as these activities extend learning. This dialogue between the instructor and a learner is especially important when responding to a learner's application of new knowledge (i.e., feedback).

References

Moore, M. G. (1989). Editorial: Three types of interaction. American Journal of Distance Education, 3 (2): 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923648909526659

Explanation strategies

Explain the purpose & value of assignments

Provide clear directions and expectations

Facilitation strategies

Assume an encouraging demeanor

Approach non-participants privately

Grade on participation

Monitor breakout rooms

Invite questions

Develop a routine

Design activities for participation

Use incremental steps

References

Tharayil, S., Borrego, M., Prince, M. et al. Strategies to mitigate student resistance to active learning. IJ STEM Ed 5, 7 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0102-y

When our courses demand that first-year students move beyond memory—as they should—we need to provide structured activities to support them in uncharted territory.

Provide feedback early and often

Pose complex, real-life problems, questions, and facilitate discussions they can relate to

Allow students time to write: Offer quick writes, 1-minute papers, or just time to reflect on learning helps students process their thoughts. This is a scaffolding step to include in addition to wait time to capture students who need more time to think.

Think-Pair-Share: This is an incredible strategy for any class of any size and it only takes a few minutes. After posing a thought question or problem, give students a minute or two to think on their own, then have them pair with a student nearby and share thoughts. Have them identify points of agreement or misalignment. In some cases, this can lead to a large classroom discussion. This is the simplest strategy to increase classroom equity as a "Think-Pair-Share" provides students time to verbalize their thoughts, promotes comparison of ideas among peers, and boosts participation and collaboration rather than competition.

Do not try to do too much: Most faculty attempt to do it all and this will inevitably lead to instructor burnout and student confusion. Choose a few things to implement and intentionally integrate them. Determine which concepts or skills are most difficult to learn, and choose techniques that will address those needs instead of trying everything.

Hand raising: Be explicit about the use of hand raising in class and create class norms around its use. Ask students who have not participated to raise their hands only.

Multiple hands, multiple voices: To encourage the voice of more students in the class, wait for multiple hands and call on the third. In a large class, encourage a "one and done" policy where once a student offers an answer they are done for the day. Remember, questions are always encouraged!

Random calling: Use index cards or popsicle sticks to write students names (this is also a great trick to learn names) and cold-call on students. Make sure to establish expectations about the use of random calling and give students an opportunity to pass if they are uncomfortable. This keeps students on their toes and listening. Once a student has participated, put their name in a discard pile until next time.

Assign roles for groups: When creating group work, make sure to assign roles (e.g., reported, facilitator, time-keeper, note-taker, etc.). Rotate roles and base them on visible characteristics (e.g., length of hair) or "get-to-know-you" information (e.g., who woke up the earliest). This is a simple strategy to improve group work and create equitable opportunities in group dynamics.

Whip (around): In small classes (< 30) have everyone share out their thoughts in 30 seconds or less.

Monitor student participation: Track who is participating and intervene if the class is being dominated by a few students. Scaffold wait time, multiple hands, etc. to encourage non-participants to speak up. In larger classes with TAs, have the TAs monitor the participation and ask them to help facilitate this. In small classes, keep track mentally.

Learn student names: This has a big impact on students, make an effort. In large classes where is may not be possible to remember everyone (> 100) have access to students' names during class for random-calling or to identify students as they participate.

Integrate culturally diverse and relevant examples: Create moments in class that students can identify with. Make it as relatable as possible.

Work in stations or small groups: Make larger classes smaller by creating groups. See our section on group work for more details on how to do this.

Use varied active-learning strategies: The "best" way to teach equitably is by providing multiple experiences for student learning. This way there is no one way to learn and students will connect with different learning techniques. See our section on active-learning for more examples.

Be explicit about promoting access and inclusion for all students: Allow this conversation to thread the class. Tell students why you are making the choices you are making. Share the effects and outcomes. Include students in your thinking about classroom inclusion.

Ask open-ended questions: One way to quickly have students check out is to ask "Are there any questions?" and yet this question is asked all the time. Develop questions that trigger thought and disagreement, questions that have multiple answers, or questions that are yet to be answered in the field. Ask students for their opinion.

Do not judge responses: Remain neutral when listening to students. If they are expressing a misconception, thank them for their contribution, ask others to build on the idea or offer other suggestions, and return to the misconception thoughtfully. Never penalize a student for sharing an idea, even if it is inaccurate.

Use praise with caution: By exclaiming praise for one student's idea may discourage others from offering other points. Praise is good, but be thoughtful about when to offer it.

Establish classroom community norms: Consider building these with students, establish them early, and constantly remind students they exist. Common group norms include the following: “Everyone here has something to learn.” “Everyone here is expected to support their colleagues in identifying and clarifying their confusions.” “All ideas shared during class will be treated respectfully.”

Teach them from the moment they arrive: The first day of class is essential. Learning can happen in a variety of ways, and so modeling learning for them all the time will help them see how often they have a chance to learn. Teach them about the process of learning "metacognition", even if for 5 minutes.

Collect assessment evidence from every student, every class: This sounds laborious, but it is valuable and can be automated with technology quite easily. Ask students to complete pre-assignment assessments and ask them the same questions at the end of the class to assess differences or similarities in their learning. Build online quizzes and surveys for metacognition, participation, and concept check-ins. This is also a wonderful way to amplify critical content, increase formative assessments, and collect data for education research.

References

Tanner, Kimberly D. "Structure matters: Twenty-one teaching strategies to promote student engagement and cultivate classroom equity." CBE—Life Sciences Education 12.3 (2013): 322-331.

Chat Feature – students enter a one-liner upon entry and exit - instructor provides a prompt (e.g., what new concept do you understand clearly, and which is still unclear?; In your own words, enter a brief description of ….)

Using icons in the chat room – encourage students to use thumbs up or thumbs down in response to a check for understanding.

Breakout Rooms – for group work/discussion

Polling Feature – Works much like an embedded quiz; clicker questions, or other periodic engagement activities.

CatCourses provides a good place to put asynchronous content that students can access at their convenience. Some ways of engaging students in CatCourses include:

Keep an eye on Who’s Slipping Away

Within CatCourses, you can use course analytics to monitor student engagement in the course. Using Analytics in CatCourses. This is critical now that we are in a remote environment. Pay particular attention to students who have slipped away, are inactive, and/or have failed to turn in assignments.

Reach out with a personal phone call. This is better than an email because of potential internet/connectivity issues students may be experiencing.

Provide guidelines with due dates (or by end of the semester) for getting missed assignments turned in. The change to remote instruction takes everyone some time to acclimate. If your students are struggling to submit assignments on time, consider removing penalties for late work or extending due dates.

Make sure students understand that even if they have opted for a P/NP grade, they must complete all work AND do so at a C- level. Incomplete work or failure to complete assignments and exams will automatically result in a zero grade – this could significantly decrease overall points in class, and therefore, one’s ability to pass the course.

Discussion Board Feature – This actually provides students with more time for reflection and the development of their thoughts/responses.

Group assignments can be used for small group work like problem-solving. Capturing group work on a GoogleDoc can be useful

10 Tips for Effective Online Discussions | Educause Review - Tips to help educators ensure that online discussions are engaging and beneficial for students. Explore the list here.

51 Student Exercises from Sociology Through Active Learning

Sociology Activity Examples | Adaptable for Online

Explore these sociology exercises from Stanford Sociology

Digital Labs and Simulations for Science and Math

An online resource that generates interactive simulations. Access it here.

From physics to biology, and beyond, this website provides information regarding digital labs and simulations. Read it here.

UCLA has created a curated list of resources for migrating labs to an online format. Read it here.

Benefits: Creates community and may increase the sense of belonging; reduces grading load; if using zoom, this addresses the challenge of using breakout rooms with 100+ students.

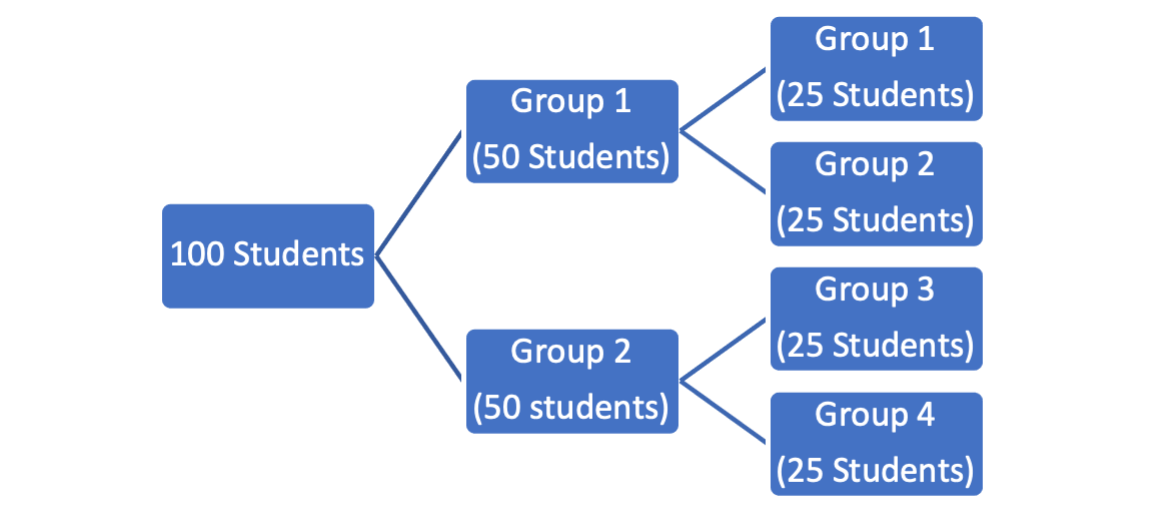

The large group of students can be divided into groups that serve as smaller communities that meet regularly. These same groups meet throughout the entire semester, working together on discussion board posts, offering peer editing and/or feedback on assignments, and even meeting for required office hours as a check-in (e.g., 20-minute intervals). TEAMs can be used for small group assignments. This provides students with an opportunity to get to know a smaller group of peers, thereby building a sense of community and ongoing support.

The large group of students can be divided into groups that serve as smaller communities that meet regularly. These same groups meet throughout the entire semester, working together on discussion board posts, offering peer editing and/or feedback on assignments, and even meeting for required office hours as a check-in (e.g., 20-minute intervals). TEAMs can be used for small group assignments. This provides students with an opportunity to get to know a smaller group of peers, thereby building a sense of community and ongoing support.

Establish a Climate Conducive for Group Work

Reduce student anxiety (especially for marginalized students with hidden identities):

Assign groups rather than have students self-select group members

Create agreed-upon norms for expected student and instructor behaviors and communications

Establish group roles, one of which is a reporter

Be clear about course (and group) expectations; give clear directions

Don't assume students possess skills necessary for effective and respectful group work.

Large classes require rigid routines and regular schedules.

Develop a system for attendance (clickers, live quiz/survey in CatCourses during lecture, etc.)

High-functioning groups are made up of 5 people.

Establish group rules/norms for respectful communication and interaction.

Assign roles to increase ownership and participation (e.g., group/task manager, equity officer [assures all members contribute], reporter, note-taker, time-keeper, devil's advocate, etc.).

Establish the purpose/value of group discussions/the discussion board.

Ensure prompts are interesting and meaningful; connected to the course learning outcomes.

Establish the expectation for supporting opinions/perspectives and advancing the conversation in each post.

Assign participation points rather than grading the content of each entry or consider grading the overall quality of the group discussion.

Use rubrics! It saves time and helps mediate feedback.

In peer review, provide sample papers/discussion posts and have students practice using the rubric. Doing so can greatly enhance assessment literacy levels and student performance on similar tasks (Smith, et al., 2013).

Though the Canvas peer review grade does not feed into the grade book, you can create a low-stakes survey to populate a grade and help you identify that a peer review was received by each student, highlighting intervention opportunities.

Host grading meetings for TAs where the group can discuss exemplars, mediocre, and poor papers and have each TA grade and comment on each one. This will normalize TA grading.

Divide grading sections on one assignment to reduce TA bias.

Have a system in place for managing complaints (communicating expectations, outcomes, and rubrics with students will reduce this time).

Ask for written complaints to deter visceral responses with 24 hours.