-

Aligning Assessment and Learning Activities

-

Task Analysis and Assignment Planning

-

Rubrics Clarifying Performance Expectations and Grading Criteria

-

Designing Rubric

-

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Course Design Rubric

Aligning Assessment and Learning Activities

From the student's perspective, what we assess signals what we think is important and what we want students to learn; it defines the actual curriculum. For example,

-

If our course assessment plan consists primarily of multiple-choice tests requiring recall of information, this tells students to focus on learning specific information (i.e., shallow learning). If our assessment plan requires students to work through cases in which they propose not only solutions but also their rationales, this sends a message that deep learning (i.e., critical thinking) is important (Saroyan & Amundsen, 2004, 97).

How students perform on an exam or final performance is as much a reflection of what they were asked to do during the learning process as it is about the design of the assessment itself. For example, students often take notes during a live or recorded lecture, complete recall-oriented assignments and/or performances, participate in discussions, and complete multiple-choice quizzes or iClicker questions to master the learning outcome and prepare for the upcoming exam. But unless these multiple-choice items assess conceptual understandings or require the application of new information, student learning will be shallow and focus on memorization for recognition purposes (Ambrose, et al., 2010; Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000). Too often, the type of questions posed to students on quizzes, polling exercises, or practice assignments does not prepare students for exam questions that require them to solve authentic, real-world problems, evaluate policies, or produce creative works.

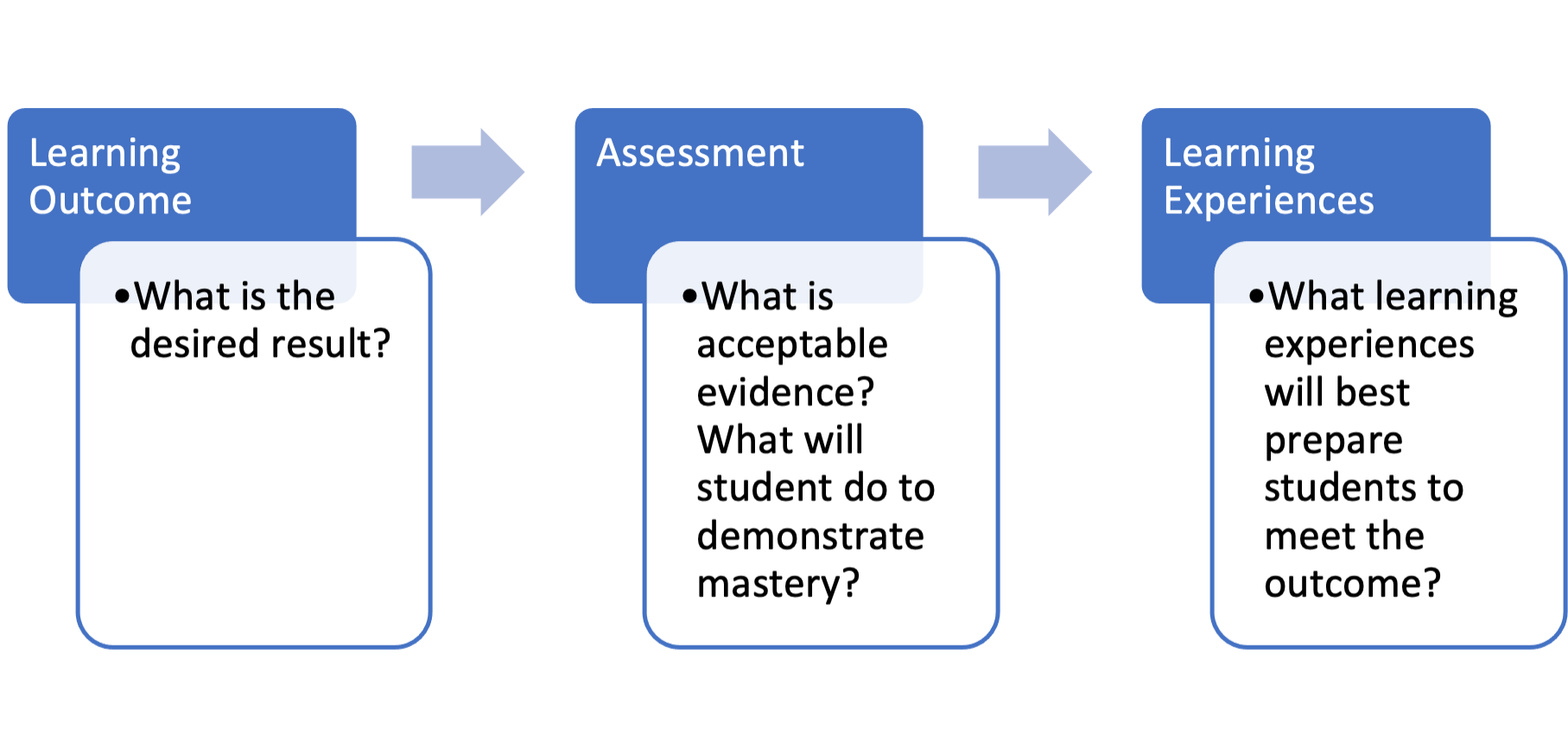

For any type of classroom assessment measure to be valid, it must measure learning that is stated in the course learning outcomes (CLOs). And from a design perspective, learning outcomes and assessments drive the selection of planned learning experiences, including content delivery, practice assignments, quizzes, discussions, etc. (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005).

When a course is designed coherently, the planned learning experiences "provide students with sufficient practice and feedback to enable them to accomplish the desired learning and be prepared for evaluation activities" (Saroyan & Amundsen, 2004, 98).

To Do:

Take an honest look at course alignment. Ask yourself the following:

-

Are the CLOS clear, observable, and measurable statements of expected knowledge, skills, and dispositions?

-

Do CLOs reflect core concepts and competencies for the level of this course (i.e., intro., lower or upper-division, graduate-level)?

-

Do you have a variety of formal and informal assessments, with more frequent formative assessments to monitor and direct student learning?

-

Taken together, are the assessments a solid reflection of the CLOs/expectations for students?

-

Do the planned learning experiences (LEs) for your course (i.e., content delivery, practice exercises, discussions, group work, assignments, etc.) adequately prepare students for the type of summative assessment utilized in each unit of study.

-

Do your assessments target lower- or higher-order thinking skills?

-

Are there ways you can improve the alignment of the LEs and assessments?

References:

-

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

-

Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L., & Cocking, R.R. (2000 Eds.). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1st edition.

-

Saroyan & Amundsen, (2004). Rethinking teaching in higher education: From a course design workshop to a faculty development framework. Sterling, VA: Stylus Pub.

-

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd Ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Task Analysis and Assignment Planning

Student success begins with a well-planned assignment that aligns at least one of the course outcomes and clearly articulates what you want students to be able demonstrate that they know (i.e., core concepts and/or competencies). Recent research has shown that providing students with a clear and transparent picture of the assignment (e.g., previous student work samples, a grading rubric) before they start the assignment can lead to better performance (Winkelmes, et al., 2016).

Consider making task analysis* a graded part of the assignment. Using the following handout, have students articulate in writing

- the purpose and goal of the assignment,

- how this task fits with previous course readings, lectures, activities,

- what steps they need to take to successfully complete the assignment, and

- exactly how they will accomplish those steps.

Finally, taking a few minutes of class time to remind students what they should be doing for their assignments can pay off down the road Gooblar, 2019).

* Task analysis is the process of breaking a task or skill down into smaller, more manageable steps or actions.

- Reread the assignment prompt.

- What are the goals of this assignment? What will you achieve or understand if you complete the assignment successfully? What will you need to demonstrate to satisfy the assignment requirements?

- Write down the specific steps you will need to take to successfully complete the assignment.

- Go through the list of steps and note next to each the time you think it will take to complete the step.

- Given the assignment due date, make yourself a plan: a schedule for completing each step in the assignment. Try to be realistic, given your other commitments, academic or personal.

- Share this plan with at least one peer to get feedback (optional).

References

- Gooblar, D. (2019). The Missing Course: Everything They Never Taught You About College Teaching. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press.

- Winkelmes, M. et al. (2016). A teaching intervention that increases underserved college student success. Peer Review, 18 (1/2), 31-36.

Rubrics Clarifying Performance Expectations and Grading Criteria

Have you ever heard any of the following from your students?

-

Why did you give me this grade?

-

You didn't even lecture about that topic!

-

You never told us that we would be graded on spelling or grammar!

-

How were we to know you wanted X?

-

Susie and I studied together, yet you gave her an A and I got a C. Why?

For most faculty, grading (sometimes referred to as marking) is one of the most undesirable aspects of the job. To promote student growth and development, grading requires providing students with frequent and instructive feedback, both of which can be time-consuming and present other challenges. According to Saroyan & Amundsen (2004), most instructors are concerned with how to

-

manage assessment and grading in large classes

-

grade group work and class participation

-

increase reliability among multiple graders (TAs)

-

increase objectivity when marking

-

handle grading disputes (95).

While these are all important issues related to grading, we want to focus your attention on one specific grading technique - the development and use of rubrics, which have the potential to mitigate many of the concerns noted above. Additionally, grading rubrics can be used to assess a range of activities in any subject area.

To Do:

Reflect on the following questions and resources:

-

What is a grading rubric?

-

A rubric is an explicit set of criteria used for assessing a particular type of work or performance, and it provides more details than a single grade or mark. Rubrics, therefore, will help you grade more objectively and efficiently (Stevens & Levi, 2005).

-

-

What are the benefits of using a grading rubric?

-

Rubrics are useful for instructors and students alike:

-

-

Instructor Benefits

Rubrics:

Student Benefits

Rubrics:

help clarify and communicate assessment/performance expectations

help clarify assessment/performance expectations; clarity on what constitutes different levels of performance (grades).

provide more objective, consistent, and equitable grading of a range of student performances, assignments, and learning activities

if given to students along with the assessment/assignment, a rubric can show students how to meet expectations, making students more self-directed in their learning

ensure timely and constructive feedback

provide feedback that is more detailed, instructive, and specific in terms of how to improve one's performance on revised or subsequent work

can reduce grading time

increases the likelihood that students will include required elements of an assignment

can help to rationalize grades when students ask about your method of assessment (reduce grading disputes)

help illuminate specific areas where the student may need to exert more effort or improve skills.

provide a vehicle for increasing reliability among multiple graders (especially if you conduct grading calibration exercises).

serve as good documentation for accreditation purposes

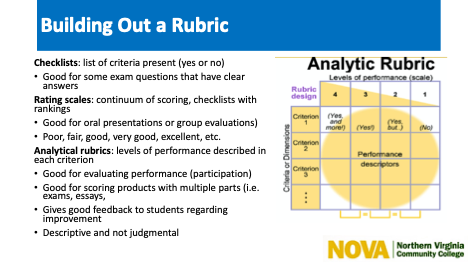

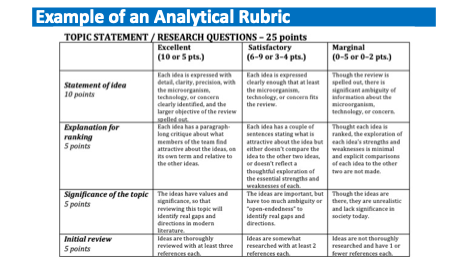

What are the elements of a rubric?

Most commonly, a grading rubric is designed in a matrix or grid-type structure and includes grading criteria, levels of performance, the range of possible scores, and descriptors that serve as unique assessment tools for a specific assignment/assessment. There are different types of rubrics (e.g., checklists, rating scales, and analytic), each serving a different purpose (see Figure 1). The most common, however, is the analytic rubric (see Figure 2).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Designing a Rubric

Identify Criteria identify the specific features or dimensions which will be measured and include a definition and example to clarify the meaning of each feature being assessed. The number of criteria to be scored will vary by each assignment or performance. For example, criteria for a term paper rubric may include:

-

Introduction

-

Thesis

-

Arguments/analysis

-

Writing conventions: Grammar, punctuation, spelling

-

Internal citations

-

Conclusion

-

References

Levels of Performance clarify the degree of performance and are often labeled as adjectives that describe the performance levels. These levels tell students what they are expected to do to achieve a particular score/grade. adjectives used for levels of performance may influence a student's interpretation of performance level. Some examples are:

-

Excellent, Good, Fair, Poor

-

Master, Apprentice, Beginner

-

Exemplary, Accomplished, Developing, Beginning, Undeveloped

-

Complete, Incomplete

-

Yes, No

-

Scores represent the values used to rate each criterion and often are combined with levels of performance. You will want to begin by asking yourself how many points are needed to adequately describe the range of performance you expect to see in students’ work. Consider the range of possible performance level (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or 2, 4, 6, 8 or a range 12-15, 9-11, 6-9, etc.)

-

Descriptors are explicit descriptions of the performance and show what is expected of the students and how scores are derived. Descriptors spell out each level of performance for each criterion and describe what performance at a particular level looks like. Descriptors should be detailed enough to differentiate between the different levels and increase the objectivity of the rater.

To Do:

What does the final grade in your course represent? In other words, how would you describe the difference between the student who leaves your course with an "A" and the student who leaves the course with a "D?" How might you help students understand performance differences and set themselves up for success in your course?

Identify at least one assessment in which a grading rubric makes sense. Create a grading rubric for this assignment. (Make sure to give this to the students before they complete the assignment.)

References:

-

Saroyan & Amundsen, (2004). Rethinking teaching in higher education: From a course design workshop to a faculty development framework. Sterling, VA: Stylus Pub.

-

Stevens, D. D., & Levi, A. J. (2005). Introduction to rubrics: An assessment tool to save grading time, convey effective feedback, and promote student learning. Sterling, VA: Stylus.