Getting Started with Backward Design

Writing High-Level Outcomes Using Bloom's Taxonomy

Core Concepts: Reducing Cognitive Load, Not Rigor

Getting Started with Backward Design

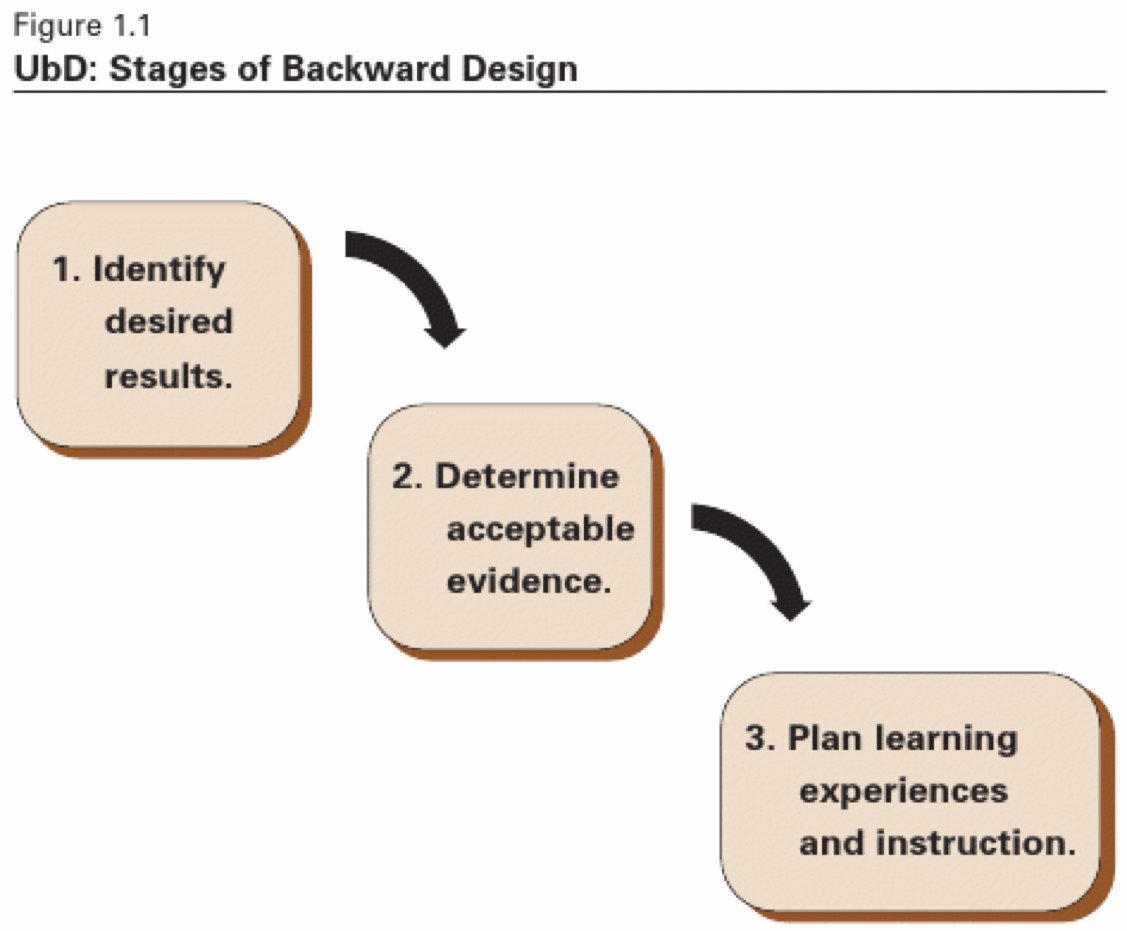

What is Backward's Design (Wiggins & McTighe 1998; Bowen 2017)? Rather than focusing on "how" to teach content, instructors should spend time identifying desired results of student learning and develop assessments to meet these goals. What do you want students to take away from the course? What skills should they develop? These are core concepts and competencies.

What is Backward's Design (Wiggins & McTighe 1998; Bowen 2017)? Rather than focusing on "how" to teach content, instructors should spend time identifying desired results of student learning and develop assessments to meet these goals. What do you want students to take away from the course? What skills should they develop? These are core concepts and competencies.

Step 1: Identify desired results.

Examples of core concepts and competencies (adapted from informED):

- critical thinking

- problem-solving

- knowledge application

- creativity

- communication and collaboration

- leadership

- global and cross-cultural awareness

- intrapersonal skills (e.g., self-direction, motivation, and learning how to learn)

Step 2: Determine the acceptable evidence.

How will students be able to know they have succeeded in learning the core concepts and competencies? How will you, as the instructor, know they have met the goal? Consider various forms of both formative and summative assessment (see more in the assessment tab below).

Step 3: Map the course learning experiences, instruction, and assessment.

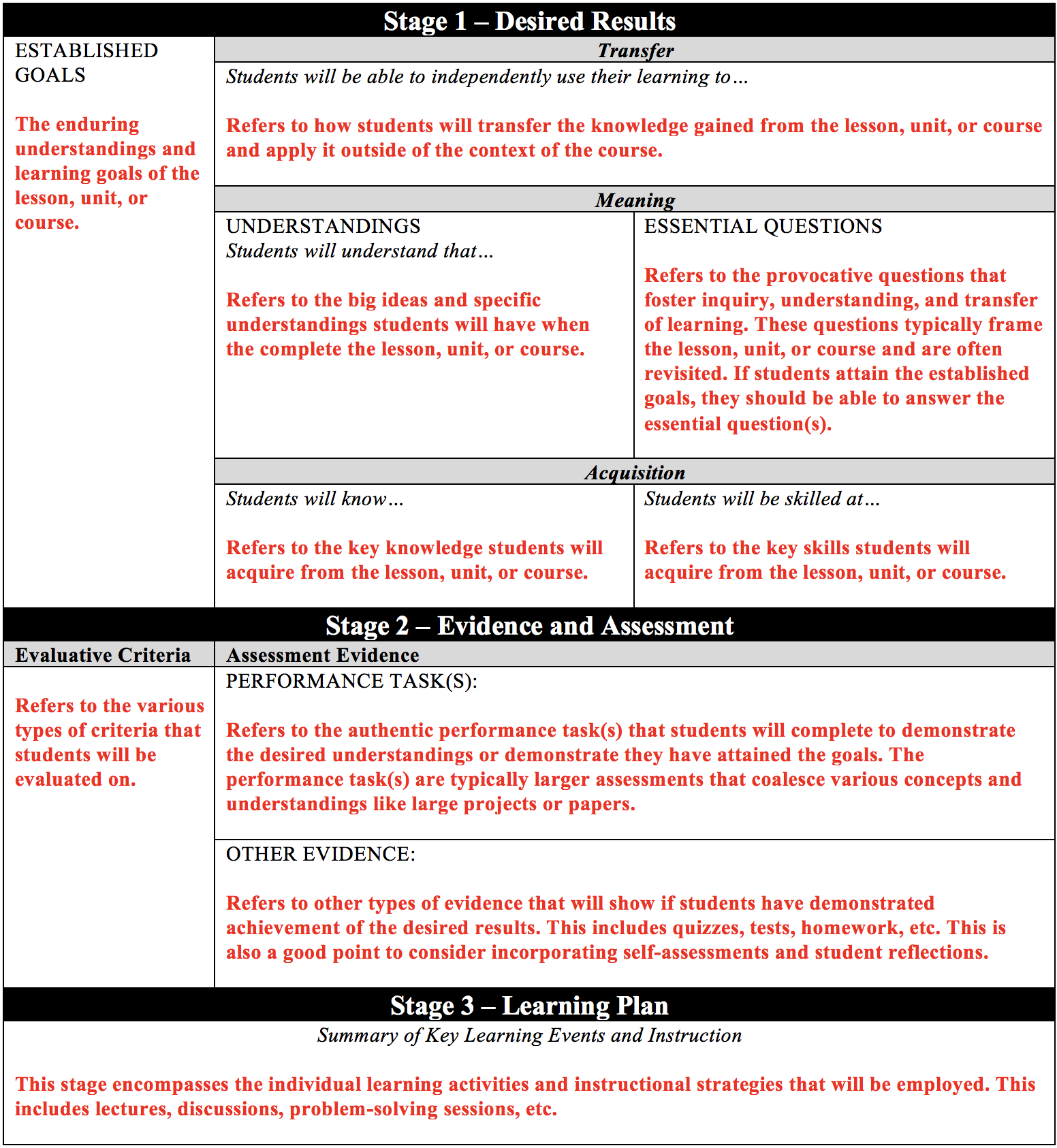

Review the template below. In this template, think of goals as the course learning outcomes (CLOs), the essential understandings as the core concepts and competencies, and performance tasks as the learning objective.

Consider the content. Do students need to know this to succeed in obtaining the core concepts and competencies? By creating a curated framework, instructors can teach students how to learn in the discipline rather than focusing on content coverage (Peterson et al. 2020).

References

- Bowen, R. S. (2017). Understanding by Design. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved [todaysdate] from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/understanding-by-design/.

- Petersen, Christina I., et al. "The tyranny of content:“content coverage” as a barrier to evidence-based teaching approaches and ways to overcome it." CBE—Life Sciences Education 19.2 (2020): ar17. https://www.lifescied.org/doi/10.1187/cbe.19-04-0079

- Wiggins, Grant, and McTighe, Jay. (1998). Backward Design. In Understanding by Design (pp. 13-34). ASCD.

Writing High-Level Outcomes Using Bloom's Taxonomy

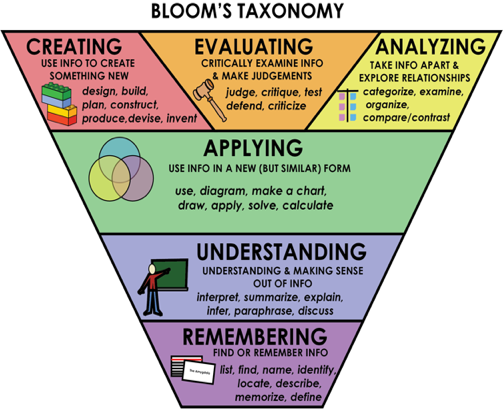

In 1956, Benjamin Bloom with collaborators Max Englehart, Edward Furst, Walter Hill, and David Krathwohl published a framework for categorizing educational goals: Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Familiarly known as Bloom’s Taxonomy, this framework has been applied by generations of K-12 teachers and college instructors in their teaching. A well-written learning outcome will help you determine appropriate assessment tasks and plan appropriate and targeted learning experiences.

In 1956, Benjamin Bloom with collaborators Max Englehart, Edward Furst, Walter Hill, and David Krathwohl published a framework for categorizing educational goals: Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Familiarly known as Bloom’s Taxonomy, this framework has been applied by generations of K-12 teachers and college instructors in their teaching. A well-written learning outcome will help you determine appropriate assessment tasks and plan appropriate and targeted learning experiences.

Learning outcomes and/or objectives should target complex skills and knowledge, by implementing Bloom's terminology into a learning outcome instructors can help students understand what they need to do in order to meet the desired results.

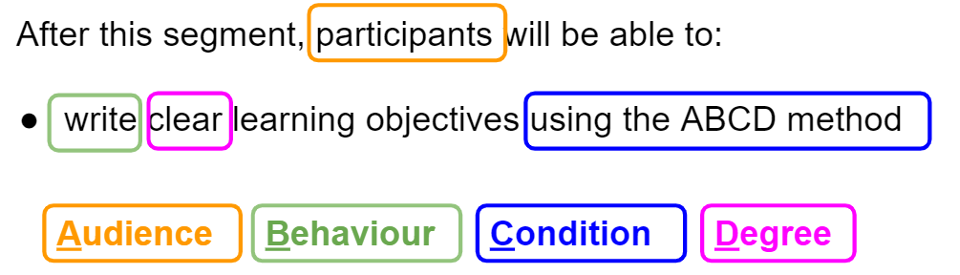

When writing these outcomes and/or objectives, follow the ABCD standard:

- A – Audience: who is the target audience?

- B – Behavior: what is it that you expect?

- C – Condition: Is there a particular method they should use to perform the behavior (e.g., given an example, using a rubric/template, or protocol)?

- D – Degree: To what extend is the behavior performed?

Practice this technique using this worksheet.

References

- Anderson, Lorin W., David R. Krathwohl, and Benjamin S. Bloom. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing : a Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives / Editors, Lorin W. Anderson, David Krathwohl ; Contributors, Peter W. Airasian ... [et Al.]. Complete ed. New York: Longman, 2001. Print.

- Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

- Image source: Rawia Inaim / Kwantlen Polytechnic University

Core Concepts: Reducing Cognitive Load, Not Rigor

We have known for some time that high levels of stress and anxiety can wreak havoc on our overall health. In cognitive psychology, cognitive load refers to the amount of resources in working memory that are being used by students for processing and encoding new information. We understand that some level of difficulty and challenge is beneficial during the learning process, but when cognitive load is too high, frustrations rise, comprehension suffers, and some students give up completely. Reducing excessive and/or extraneous cognitive load is completely in the hands of the instructor.

In 2017, Malamed, an e-learning coach, argues, “by reducing the extra mental effort required to learn new information, we can assure greater learner success” (Malamed, 2017, Par. 3). While we have little control over the demands placed on our students outside of the educational environment, we can take steps to reduce the extraneous load placed on students during the learning process.

Five Strategies to Reduce Cognitive Load (adapted from Malamed 2017)

Amplify Critical Content

- What knowledge, understandings, skills, and dispositions associated with your course are essential (i.e., it would be a travesty if students left your course without mastering this content)? What extraneous information may be causing unneeded complexity and distraction for your students? By removing some of the unnecessary material, even if you believe it is important and/or worth students being familiar with, you can reduce the demand on the limited cognitive resources available in working memory and set students up for success. Amplify the essential content associated with your course learning outcomes

Communicate Concisely

- Communicating concisely is another way to reduce cognitive load. In the case of writing, especially instructions, more is not necessarily better. Choose your words carefully; use only those which are needed to explain, clarify, or provide direction. When it comes to content delivery, often a shorter article, text passage, or multimedia source can convey content just as well and reduce cognitive load. Reduce long periods of lecturing; employ synchronous instruction to clarify major concepts or principles, address misconceptions common to the discipline, and clarify assignment expectations.

Use Generative Strategies

- Reflection and elaboration are essential to the learning process. Have students pause to think about what they have just learned, express ideas and concepts in their own words, and elaborate on a concept by linking it to their lived experiences and/or other familiar concepts. Within a presentation of information, whether a lecture, video, or other multimedia source, embed prompts that force students to stop and reflect about what has just been presented. For example, embed active learning strategies like the minute paper; the clearest and muddiest point; explain in your own words, etc. You might have students enter a sentence into the chat window or discuss it with peers and students may be asked to contribute thoughts within a discussion class/board.

Provide Scaffolding and Cognitive Aids

- Scaffolding and other cognitive aids are instructional support techniques implemented to reduce the demands placed on working memory during an instructional event or learning task. These supports are intentionally designed to assist students as they read through complex material, research articles, and/or complete assignments, lab exercises, and simulations. Scaffolds and cognitive aids come in many forms: a checklist, a flow chart, a timeline, guiding questions, worked problems as examples, tables or concept maps revealing concept relationships, or even a quick-reference glossary for new and essential terminology. These supports can be particularly useful for group work, presentations, and projects. As students become more proficient, supports may be reduced or withdrawn. Especially in the remote learning environment, it is important to identify parts of a learning task that may present the most challenge. Then, embed appropriate supports into the learning module that students can select to use if they need extra help.

Increase Opportunities for Collaboration

- In collaborative learning, the memory demands required for the learning task are divided among several individuals. This is especially helpful with complex content or assignments. Group members will still need to re-integrate information and coordinate their learning, but group processing is believed to provide a more robust learning environment that results in deeper processing and more meaningful learning than individual work. In a remote learning environment, you can arrange collaborative learning through synchronous video conferencing and breakout rooms or asynchronous platforms such as a discussion board, blog, or social media entries.

References

-

Lukasik, K. M., Waris, O., Soveri, A., Lehtonen, M., & Laine, M. (2019). The relationship of anxiety and stress with working memory performance in a large non-depressed sample. Frontiers in Psychology, 10:4. Doi 10:3389/fpsyg.2019.00004.

-

Malamed, C. (2017). Six strategies you may not be using to reduce cognitive load. The eLearning Coach (www.theelearningcoach.com).

-

Moran, T. P. (2016). Anxiety and working memory capacity: a meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 142, 831-864. Doi 10.1037/bul0000051.

-

Plass, J. L., Moreno, R., & Brünken, R. (2010). Cognitive Load Theory. New York, New York: Cambridge Press.